The Alaska Project was not actually my first attempt at a thriller set in the present day (I had already written The Cromwell Exercise and Phoenix by then), but it was the first to be published. The idea for Alaska came from the shooting down of KAL 007, a Korean Airlines Boeing 747 with 269 people on board, by a Russian jet fighter over the island of Sakhalin in September 1983. In the immediate aftermath of the atrocity, what had seemed a fairly promising situation for détente between the Soviet Union and the USA collapsed into mutual recrimination and a hardening of attitudes – both sides increased their military budget, the SALT talks were pretty much shot down in flames, and so on. It occurred to me that KAL 007 suited the ‘hawks’ of both sides – what if they had planned it together? And what if they combined once more in the 1990s to undermine the process of glasnost?

The Alaska Project was not actually my first attempt at a thriller set in the present day (I had already written The Cromwell Exercise and Phoenix by then), but it was the first to be published. The idea for Alaska came from the shooting down of KAL 007, a Korean Airlines Boeing 747 with 269 people on board, by a Russian jet fighter over the island of Sakhalin in September 1983. In the immediate aftermath of the atrocity, what had seemed a fairly promising situation for détente between the Soviet Union and the USA collapsed into mutual recrimination and a hardening of attitudes – both sides increased their military budget, the SALT talks were pretty much shot down in flames, and so on. It occurred to me that KAL 007 suited the ‘hawks’ of both sides – what if they had planned it together? And what if they combined once more in the 1990s to undermine the process of glasnost?

Thus, The Alaska Project started with the shooting down of KAL 007 with the aerial sequence being based on the actual signals sent and received by the Soviet Air Defence System and Major Kasmin, the pilot of the fighter that shot down the 747. (There are stories that Kasmin later descended into alcoholism and died in his 50s from liver disease.) The narrative then moves on to 1995 (the book was published in 1989) to take up the story – in other words, projecting the global political situation at the end of the Eighties into the near future. It was an approach that seriously backfired in the end, but more of that later.

The story needed two protagonists, one British, one Russian, because there would be two storylines developing, one in the West, the other in the Soviet Union; eventually, the two would dovetail together. This probably turned out to be an error of judgment on my part in terms of appealing to a global audience because not only was neither of the heroes American, the main villain was – hardly an approach likely to appeal to a US audience. I suspect that this is why Walker Books decided not to buy Alaska’s US rights (although there were other, equally valid reasons which are outlined below). However, at the time of writing Alaska, I admit I was not really thinking that far ahead.

So: two main characters – Peter Kendrick, working for Desk Seven, a fictional offshoot of MI5, and Ilya Voronin, an experienced officer in the First Chief Directorate of the KGB, the department responsible for foreign espionage. Both experienced professionals, they are forced to co-operate as the outlines of the Alaska Project gradually become clear. They actually have a good deal in common in that both men have sacrificed personal relationships due to the demands of the job, but they only ever meet twice face to face in the book; apart from that, they must work independently.

The Alaska Project probably involved more research than any other book – there are sections set in the headquarters of the CIA in Langley, Virginia and in the corresponding HQ of the KGB (which wasn’t still in the Lubyanka, actually); I also needed detailed information about Soviet military helicopters, guided missiles and ASAT (anti-satellite) techniques, along with information about the internal structure of the KGB. The thought has often crossed my mind that if anyone monitors this sort of research, I’m probably on some sort of security file by now…

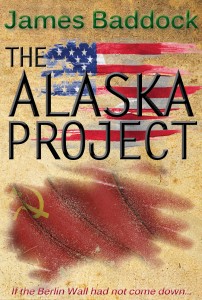

Alaska ended up as a long book; 115,000 words as opposed to 70 to 80,000 words for the others (and actually twice as long as The Faust Conspiracy in its original version) and it was also a book that I hoped would reach a larger audience, but it was plagued by setbacks and problems almost from the start. The original cover artist ended up withdrawing the cover (on the not unreasonable grounds that he hadn’t been paid) and so a replacement artist had to be drafted in, then there was a nine month delay in publication because of a dispute with the printers (I suspect for the same reason as the artist’s withdrawal) and the book actually went out littered with typos (some of which I could clearly remember correcting at the proof reading stage, so heaven knows what happened there, because I don’t…) Worse than that was that the ending was rewritten by the publisher without my approval; the change was only in a couple of sentences, but it left most readers bewildered – what had actually happened? The final calamity came within three months of the book eventually being published, when the Berlin Wall came down in November 1989 and the political map was changed forever; there is a sequence in Alaska that refers to Checkpoint Charlie… in 1995. OK, so bringing down the Berlin Wall wasn’t a calamity from anyone else’s point of view, of course, but it cut whatever ground the book had left from under it. So, far from being my springboard to writing success, The Alaska Project disappeared into utter obscurity – it actually sold fewer copies than any of its predecessors. This was not just down to the fact that it had become outdated, however; the publishing company was in quite serious financial straits by then and so the book’s distribution was piecemeal at best. The fact that the book was outdated within three months of publication was also probably the other reason why it never found an American publisher (see above).

In short, one way or another, The Alaska Project became the biggest disappointment in my writing career – it still is, to be honest. It was to be the last book of mine to be published in the UK – the next, Piccolo, would only be published in the USA and Canada (and sold about six times as many copies as Alaska.)

Initially, when I came to revisit the books in order to release them as ebooks, I was not going to include Alaska – it dealt with a 1995 that never existed, after all. However, it’s still a book that I feel proud of, so I decided to approach it as an ‘alternative history’ novel – what might have happened, rather than what actually did. Once that decision had been made, the main alteration initially made to the book was to add a sequence giving more insight into Voronin’s character and backstory (apart from correcting the typos and restoring my preferred ending, of course). However, upon further re-reading, it became apparent that the romantic sub-plot between two of the main characters just wouldn’t have happened, for all sorts of reasons, so that had to be written out. However, it wasn’t as if leaving out that storyline was going to have any significant impact on the book’s length – it still weighs in at nearly 110,000 words. In addition, it made no difference to the overall story (which was another reason for leaving it out – it wasn’t exactly essential).

In some ways, I’m looking forward more to Alaska coming out as an ebook than any of the other print versions; it’s finally the way I want it and it will be available to far more readers than the first time round. In theory, anyway; whether they will actually read it is another matter, of course…